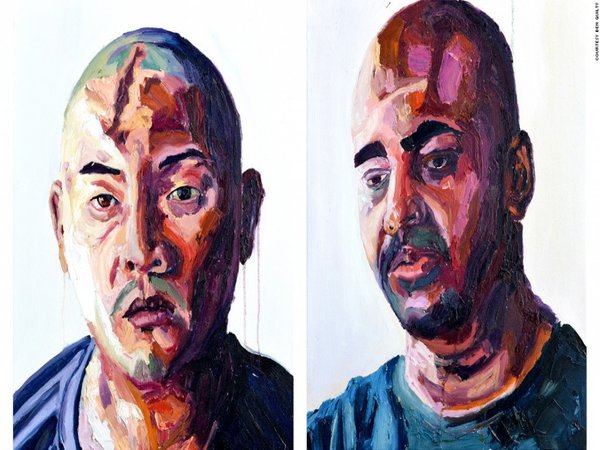

Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran were executed by firing squad last Wednesday for their role in a 2005 drug smuggling plot in Indonesia.

Their attempt to smuggle around $4 million worth of heroin into Australia is a crime that could have affected, or put an end to, the lives of thousands.

Despite the serious nature of the crime, the two have since been hailed by many as heroes.

Candlelit vigils were held in their honour and Australian celebrities campaigned to “bring our boys home“.

#Bali9: Sydney vigil for Andrew Chan, Myuran Sukumaran calls for mercy, draws 200 people http://t.co/61vSv5Qefo pic.twitter.com/6EEkfB6QbZ

— ABC News Sydney (@abcnewsSydney) April 27, 2015

Since their deaths, the Australian Catholic University has created a scholarship for Indonesian students in the name of the duo.

ACU Vice-Chancellor Greg Craven said that the scholarship was deeply symbolic and an ongoing contribution to the eventual abolition of the death penalty in Indonesia.

“The scholarships would be a fitting tribute to the reformation, courage and dignity of the two men,” he said.

Prime Minister Tony Abbott has said that the scholarship sent a very unusual message.

“We know that they were repentant, we know that they were rehabilitated, we know that they seem to have met their fate with a kind of nobility and all of that is admirable,” he said. “But whether that justifies what has apparently been done is open to profound question.”

Abbott, amongst many others, has expressed opposition to the death penalty.

Indonesian authorities have taken a hardline stance against drug offenders and have been unwavering on the use of the penalty.

Numerous attempts by Abbott and Foreign Minister Julie Bishop to halt the executions were refused by Indonesian President Joko Widodo. Widodo said that clemency would not be granted to drug offenders, which would serve as “important shock therapy” for dealers, traffickers and users.

A change in public opinion regarding Chan and Sukumaran has been evident in the mainstream media’s narrative. When the pair was first arrested there seemed to be little sympathy from the media; however, more recent coverage portrayed public outrage over the executions.

Sally Young, Associate Professor and Reader in Political Science at The University of Melbourne, tells upstart that media coverage has changed to reflect society’s shifting opinion.

“At the beginning, News Limited papers were very unsympathetic of the men and later on their coverage became far more sympathetic,” she says.

“The media were picking up on perceptions that were quite possibly changing because of the increase in detailed reporting on the topic.

“There was a lot more information about how the justice system works in Indonesia, about some of the claims of discrepancies between penalties for people who had done similar crimes, about allegations of bribery and treatment in prison.”

Young says that these commercial media companies need to reflect public opinion in their content for its audience to be interested.

“It’s always been the case that commercial media have to sell news and to do that they need to give the audience news that reflects their passions and interests, and news that they want,” she says.

“It’s also probably a democratic thing, one of the roles of the media has always been to pass public opinion up to the decision makers.”

She says that this is most likely why Fairfax ran the campaign to “bring our boys home”, which features Australian actors, musicians and writers demanding Mr Abbott “be a leader” and “fight for our boys”.

“It was pretty clear that Fairfax newspapers were doing everything they could to get public opinion to pressure the government into advocating for a better result for these men,” she says.

The Mercy Campaign distanced itself from Fairfax’s clip amid claims it was political and opportunistic. Despite these claims, a lot of people are still pledging to #standformercy in an attempt to eventually abolish the death penalty around the world.

Australians have come together in opposition to the death penalty and in support of the men they saw as rehabilitated citizens; however, the fate of Chan and Sukumaran was in the hands of Indonesia, a country struggling to combat a severe drug problem.

The representations of Chan and Sukumaran in the media arguably played a role in shaping public opinion, leading many to view the pair as heroes rather than criminals.

Joely Mitchell is in her final year of a Bachelor of Journalism degree at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter: @joelymitchell.

Joely Mitchell is in her final year of a Bachelor of Journalism degree at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter: @joelymitchell.