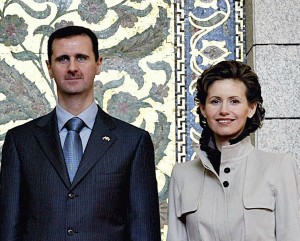

Born in London but made in Damascus, Asma al-Assad is no stranger to foreign profiles.

From fashion features and comparisons to Marie Antoinette in the Huffington Post, to reports of an influence that would make Lady Macbeth blush, Syria’s first lady is a bona fide media magnet. But of all the articles written on Asma al-Assad, none have caused more controversy than that feature published by Joan Juliet Buck for Vogue Magazine in 2011.

The feature is infamous for many reasons. It was of course the first authorised interview with Asma al-Assad. The story was the result of a carefully crafted public relations campaign launched by Brown Lloyd James.

But the story made headlines for its complete acceptance of crafted spin from the charmer herself, for its disregard for repression within Syria, and for its publication at the height of the Arab Spring.

From the moment the story hit the print, Joan Juliet Buck was subjected to a barrage of criticism from all corners of the globe. It appeared the Vogue reporter had drunk from the Assad punch bowl, and in the face of Arab rebellions the world wasn’t buying it.

In April 2011, Vogue eventually removed the piece without comment, until pressed later for a disclaimer. It’s editorial staff have been dealing with the mess ever since.

To understand the commotion we need to remind ourselves of the timing.

The piece was published on February 25, 2011. Eight weeks prior, a fruit vendor by the name of Mohamed Bouazizi lit himself alight and the protests that followed became the Jasmine Revolution.

Four weeks prior, a Facebook group called for renewed revolution in honour of Khalid Said, a young computer programmer who was dragged out of a cyber café in Tahrir Square by security forces and beaten to death in June 2010. Egypt’s disparate communities galvanized in unified protests in Alexandria and Tahrir Square.

At the time of publication President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali had fled Tunisia for Saudi Arabia, while Hosni Mubarak resigned in Egypt only fourteen days earlier.

In the midst of this upheaval stood the Vogue feature; a glowing indictment of a despot’s wife cast by an American as a crusader for community cohesion, as an embodiment of Western style, a study in orientalism, and an expression of the West’s selective attention.

Until Tuesday last week, Joan Juliet Buck remained largely silent, with the exception of the odd interview. Her silence was broken in a seven-page feature for Newsweek, in which she laid blame solely at the doors of her Vogue editors and the ploys of Asma al-Assad.

Describing scenes of anxiety, Buck refers to her continual pleas for the story to be scrapped that were ignored by her editors. Despite this, she continued to write the feature as ‘I always finished what I started.’

But the words of the profile were her own. They may have been exactly as the Assads desired, but the feature was ultimately of her crafting.

The real problem is that Joan Juliet Buck’s justification lacks accountability. Her portrayal of herself as a victim of Vogue editors and her own naivety is a mockery that is almost as offensive as her initial misgivings.

There’s an old saying that an editor will make themselves your worst enemy. Anyone who’s brought this excuse in recent days forgets that what a journalist writes below the byline is their own responsibility, their own craft, and their own words.

The story may have been published against her final objections, but no one wrote those words on the page other than Joan Juliet Buck – even if they were spun with the charm of Asma al-Assad.

Joan loses her audience when she repeats the same insensitive mistakes that she accuses her editors of tarnishing her name with; a blissful disregard for the state of affairs in Syria. It makes you wonder whether her story is even the least bit credible.

Look at the timing of the Newsweek response. It was only six weeks ago that we saw televised footage of butchered children during the siege of Houla.

Even more recently, we watched the Syrian Free Army move on Damascus and fixed-wing fighters flying above the capital. The regime is now reported to be using artillery and aircraft to attack the Syrian Free Army within Aleppo.

Since March 2011, The Guardian has reported that 22,805 people have died based on data from Syrian Schudad. Human Rights Watch has also revealed 27 secret torture centers through its own investigations.

So here stands Buck’s defence, free from the restrictions of Vogue editors yet once again imprisoned by a narrow focus and insensitivity.

If nothing else the timing of her response reveals her true concerns. They are not for the people of Syria, they are not for ‘the boys’ or ‘young teenagers’ at Massar, they are for her own skin, her own reputation. These are of course the very concerns that were the focus of earlier criticisms.

So horrified at injustice of the situation, she decided to write a seven-page account of her betrayal by Vogue’s editing staff: A martyr of the Vogue newsroom.

Focus not on the ongoing tortures of the Assad regime, focus not on the savagery at Homs, Houla and Aleppo, focus not on the siege of Damascus nor the continuing regime defections; but instead on the tyranny of those nasty Vogue editors in Paris.

Henry Belot is a Global Media Communications student at Melbourne University. You can follow him on Twitter: @Henry_Belot