“Fake news” has entered the lexicon over the past couple of years, spreading rapidly thanks to the internet, and especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. But sometimes, don’t you wish it would all just disappear?

Singapore has tried to make it do just that.

The Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019 (POFMA) aims to “prevent the communication of false statements of fact” and has been in force for over one year. It gives ministers in government the power to issue correction notices on online news articles or social media posts, which are published on the government’s website.

They can also remove or block access to websites or social media pages, as seen in February when the government asked Facebook to take down a page. The tech giant even said they were “concerned about the precedent this sets” for freedom of speech in the country.

The law has also come under attack for being a threat to press freedom. In 2019, Reporters Without Borders called the law “Orwellian”, one that has the potential to be a “horrifying tool for censorship and intimidation”. The NGO, who advocate for the right to freedom of information around the world, also keeps an annual ranking evaluating press freedom worldwide.

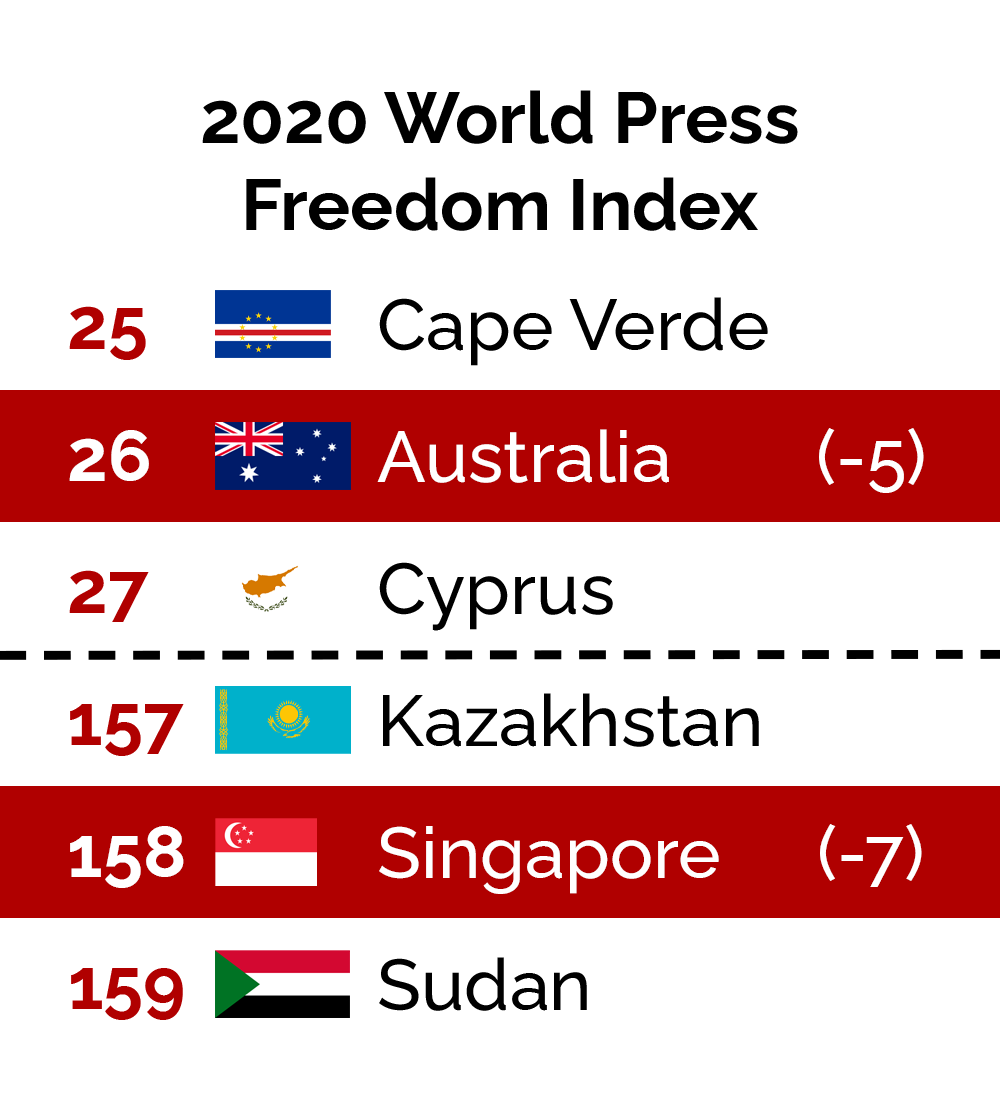

The passing of the law saw Singapore drop seven places to 158th out of 180 countries in the ranking this year.

However, it is not the only country seeing a downward shift. Australia moved down to 26th on the ranking, a slip which journalist Peter Greste says is “not too bad”.

However, new legislation intended to protect Australia from threats like terrorism or foreign interference is threatening that position even further. These laws can let authorities identify anonymous sources or whistleblowers, or even jail journalists trying to protect their interviewee’s anonymity.

The raids by the Australian Federal Police on the ABC and the home of News Corp journalist Annika Smethurst in June 2019 saw this threat to Australia’s press freedom materialise.

“The AFP raids confirmed all that we predicted,” Greste told upstart.

“National security laws [has]…criminalised, what in the past, would have been considered legitimate journalistic inquiry and overall had a chilling effect on public interest journalism”

Greste says that another issue threatening press freedom is a lack of financial resources.

“A media that is so broke that it can’t afford to hire experienced journalists to spend time investigating the government is as constrained as a media forbidden by law from making those investigations,” he said.

Despite these issues, Australia’s media landscape may seem free to the average citizen, especially when compared to countries like Singapore, where the media is tightly controlled, and a majority of television, radio and print is owned or closely linked to the government.

Singaporean journalist Kirsten Han says that people in the country have instead looked to social media or messaging apps to express themselves. However, with laws like POFMA, the government is looking to control the internet too.

“It’s not that Singaporeans don’t have outlets to express political ideas; the oppression or suppression is much more subtle than that,” Han told upstart.

“It’s that there are broad and vague laws and mechanisms that can be selectively used against individuals, thus perpetuating fear and self-censorship.”

POFMA has been seen as another one of these “board and vague” legislations that gives the government the power to restraint its citizens.

“While a correction direction under POFMA might not carry the threat of penalties like jail time, unless you refuse to comply with their order, it’s still not something that many people would want to have happen to them,” Han said.

Since 1959, the city-state has been ruled by the People’s Action Party (PAP). The party have also held more than two-thirds of the seats in parliament since 1968, meaning they can amend most of the constitution without a referendum.

According to Han, this has led to political apathy among Singaporeans, even in response to laws like POFMA.

“The idea of the PAP pushing through whatever laws or policies that they want is pretty normalised in Singapore,” she said.

“There was a strong reaction [to POFMA] from civil society, academia, and even tech companies, but I’m not sure that there was a strong reaction from the general public more broadly.”

July this year saw Singapore’s first general election with the law in force. The opposition won ten seats out of 93, their largest share in the country’s history.

“POFMA was used against a few opposition politicians but didn’t seem to have much of an effect on the election outcome,” Han said.

“It makes me wonder if people have come to see POFMA as a political tool that might not have a lot of legitimacy. It’s quite interesting that POFMA hasn’t been invoked since the end of the general election.”

The first orders of the law, when it came into force in October 2019, were seen to only be directed at opposition politicians and other critics of the government. But communications minister S. Iswaran said at the start of the year that this was only by chance.

“I would say that that is a convergence, some might say an unfortunate convergence, or coincidence,” Iswaran said in parliament.

Han says it important to keep giving people in Singapore the option to view a variety of opinions through the internet.

“Singaporeans need and deserve to have access to a diversity of perspectives and voices. We should have vibrant public discussions on issues that matter,” Han said.

“It’s important to have independent news sites be part of this ecosystem, rather than allowing our media diets to be dictated by those in power.”

Misinformation is an ongoing problem for governments.

Greste, who himself was jailed for 400 days in Egypt accused of reporting false news, says that it should be up to social media companies to stop the spread of “fake news”.

“I am convinced that the reason we are in this crisis is because of the way the digital platforms enable misinformation to flourish and spread. It is in the interests of those companies,” he said.

“That isn’t to be critical of them – their engineers have fulfilled their brief, to hold our attention and turn that into money, incredibly effectively – but they are not working for the interests of us, the society that has absorbed their technology so completely.”

Greste says that governments could regulate these platforms to prioritise fact-based journalism.

“I think it is possible, though not being a software engineer, I can’t tell you what that solution might look like,” he said.

Article: Hilman Hambali is a third-year Bachelor of Media and Communications (Sports Journalism) student at La Trobe University. You can follow him on Twitter @hilmanhambali.

Photo: Photo by Brian Jeffery Beggerly available here and used under a Creative Commons Attribution. The image has not been modified.