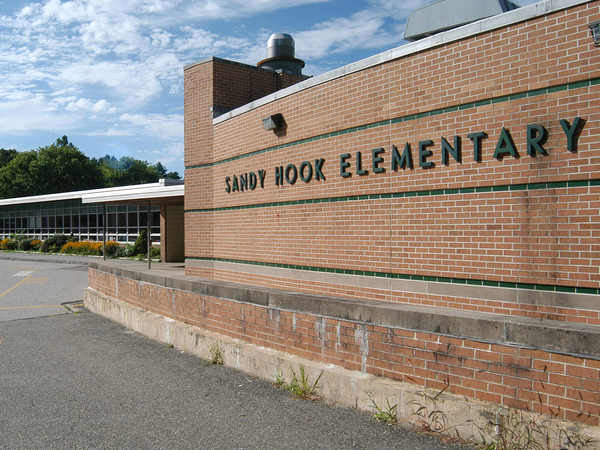

On 14 December 2012, 20-year-old Adam Lanza broke in to Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, and shot 20 children and six adults dead, before turning the gun on himself.

As disturbing information and images flooded newsrooms, journalists were forced to grapple with the question: “what should we do when children’s suffering becomes news?” The answer is unclear, a precarious balance between privacy and public interest.

Privacy

What is the ‘right to privacy’?

It is the right of a person to have their personal information protected from public scrutiny.

In Australia, the right to privacy is currently covered by the Privacy Act 1988 (Privacy Act).

In the case of Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Lenah Game Meats (2001), the High Court did not consider a separate right to privacy, but considered the option of a tort of invasion of privacy, which has not yet been developed.

Torts, or civil wrongs, are under ‘common law’, which means that a judge’s decision is based on legal precedent rather than legislation.

What is the Privacy Act?

It is a law that outlines how agencies (ministers, departments, federal courts, or other public bodies) and organisations (individuals, body corporates, partnerships, or unincorporated associations or trusts) must handle and process personal information.

What is ‘personal information’?

It is any information that identifies a person, or could identify a person, including their name, address, signature, telephone number, banking details and medical records.

Do children have the ‘right to privacy’?

Yes, they do. The right to privacy of children is covered by the Privacy Act, but it does not specifically relate to them.

Do deceased persons have the ‘right to privacy’?

Paul Roth, a leading researcher in privacy law and author of Privacy Law and Practice, says:

“It is normally accepted that in law, deceased persons have no privacy interests. This is presumably on the basis that the raison d’être for privacy protection no longer exists, since dead people can feel no shame or humiliation.” The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) believes that the Privacy Act should be updated to include protection for the personal information of deceased persons, although they ‘feel no shame or humiliation’.

It recommends that the use and disclosure of their personal information, access by third parties, data quality and data security, be regulated in the Privacy Act.

Agencies and organisations should take “reasonable steps” to ensure that such personal information is “accurate, complete, up-to-date and relevant (data quality)” and protected from “misuse and loss and from unauthorised access, modification or disclosure (data security).”

They were also encouraged to “respect the sensitivities of family members when using or disclosing [such information]” in a review by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC).

Does a person have the right to sue for a breach of privacy?

In Australia, a person cannot sue for an invasion of privacy because there is no law that covers an invasion of privacy.

Peter Gregory, a journalism lecturer at La Trobe University, tells Upstart that “other related laws get interpreted to have the practical effect of awarding damages”.

“There are cases when Australians have been awarded damages for effective privacy breaches, but when the cases get to the Supreme Court or an appeal court, reference is made to a breach of confidence,” he says.

Is there a media exemption from the Privacy Act?

Yes, there is a media exemption from the Privacy Act. Section 7B states that a media organisation is exempt from the operation of the Privacy Act when they are “publicly committed to observing standards that deal with privacy” and “have been published in writing by the organisation or a person or body representing a class of media organisations (e.g. Australian Press Council)”. The New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People believes that the right to privacy of children is not adequately protected under the media exemption from the Privacy Act. It recommends that media organisations include legislative requirements that are directly related to children in their codes of conduct.

Public Interest

What is the ‘public interest’?

A media organisation might use the ‘public interest’ to defend an editorial decision, but the term is difficult to define.

The British Press Complaints Commission (PCC), superseded by the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO), describes it as the ‘common good’, which includes “detecting and exposing crime, or serious impropriety, protecting public health and safety, and preventing the public from being misled by an action or statement of an individual or organisation”.

Andrew Sparrow, a senior political correspondent for the Guardian, warns against “defining it or pinning it down” because it “could end up being restrictive” and “our view of what the public interest entails changes quite dramatically over time”.

What is the ‘privacy versus public interest debate’ in the media?

The right to privacy should be respected by the media. However, it may be necessary, even justified, for them to invade a person’s privacy in the name of public interest.

So, can children ever be identified in the media?

Yes, they can.

In Australia, there is only one section of one broadcasting guideline, the Commercial Television Industry Code of Practice, which directly relates to reporting on children.

Section 4.3.5.2 urges the media to “exercise special care before using material relating to a child’s personal or private affairs in the broadcast of a report of a sensitive matter concerning the child.”

It also recommends that they obtain “the consent of a parent or guardian… before naming or visually identifying a child in a report on a criminal matter involving a child or a member of a child’s immediate family, or a report which discloses sensitive information concerning the health and welfare of a child, unless there are exceptional circumstances or an identifiable public interest reason not to do so.”

The International Federation of Journalists’ (IFJ) guidelines for reporting on children warn the media against “visually or otherwise identifying children unless it is demonstrably in the public interest.”

They recommend that the media “obtain [their image] with the knowledge and consent of a responsible adult, guardian or carer”.

Sandy Hook: the privacy versus public interest debate

It is in the public interest to know about a tragic event like ‘Sandy Hook’, but is it in the public interest to invade the privacy of, and identify, children when it occurs?

The Daily Mail and People Magazine released photo collages of the victims in their remembrance, while CNN and NBC interviewed young survivors.

Were they right? Were they wrong? Were they ethical?

Wolf Blitzer, a CNN reporter, explains that his network “always asks permission” from a parent before interviewing their child. However, they were wrong and completely inappropriate to interview the children of ‘Sandy Hook’.

The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma warns against “interviewing a child who has just witnessed death or injury” under any circumstance because it “may add to their stress”.

Rebecca Greenfield, a reporter for The Wire, also notes that interviewing the children of ‘Sandy Hook’ provided “more ‘buzz’ than intel” because the information could have been obtained from an adult source – police officer, teacher or paramedic.

The Daily Mail and People Magazine identified, and named, the victims of ‘Sandy Hook’ through photo collages.

It is a legally and ethically complex decision: children have the right to privacy, but deceased children technically do not.

The New South Wales Information and Privacy Commission (IPC) advises the media to apply the public interest test in such cases, “weighing the factors in favour of disclosure against the factors against disclosure”.

It is arguable that the decision of the Daily Mail and People Magazine was in the public interest because it renewed the debate about gun control in the United States.

However, there is no right or wrong answer, only a more ethical one.

So, what can an emerging journalist learn from the situation?

It is important to seek advice from your editorial team when you are reporting on children.

Paul Carr, editorial director of Pando, believes that editorial discussion “adds a second layer of sanity checking”.

“On many occasions, a Pando reporter has mentioned a tip on our internal discussion system only to have a colleague point out a reason why the story isn’t what it seems,” he says.

“Often this leads to a story, but a better, more rounded one. Other times it avoids us publishing something that would have later turned out to be, at best, old news or, at worse, false.”

If you are still in doubt, refrain.

Sheridan Lee is a second-year journalism student at La Trobe University. You can follow her on twitter here: @sheridanlee7.