It’s been a rough start to 2016 for Australia’s micro-parties and their convener Glenn Druery.

In March the Coalition formed an unlikely team with The Greens to pass legislation through Parliament that has dramatically changed the way senators are elected.

The reforms effectively eliminate the Group Voting Tickets that micro parties have traditionally relied on for carefully planned preference arrangements – transferring the duty of preferencing back to some 95% of voters.

This isn’t good news for anyone called a “preference whisperer,” as Druery has become known.

Druery has been working with micro parties for two decades and has created a business model out of facilitating co-operation between minor parties through a process called “preference harvesting.”

The model may have been too successful. When preferences saw Ricky Muir and Bob Day elected to the Australian Senate in 2013 with 0.5% and 3.8% of the primary vote respectively, eyebrows began to rise.

Most of all within the Coalition, who have subsequently struggled to get their agenda past a hostile cross-bench of independents. Prime Minister Turnbull went so far as to single out Senator Muir as a part of what he called a “disgrace” of an election.

But Druery and the micro parties are no strangers to unlikely teams.

The mish-mash of parties from the left and right of Australian politics are now focused on payback, announcing plans to launch a counter-campaign in marginal lower house seats important to the Coalition and The Greens.

In March Druery organised a meeting of the Minor Party Alliance, a body of 30 minor parties from across Australia, to affirm support and formulate a plan of attack.

The alliance plan to use diversity to their advantage, with Druery encouraging progressive member parties to run candidates in electorates that the Greens are targeting and right wing parties to single out important Coalition seats.

The message is clear: participating minor parties will preference Labor above Coalition and Greens candidates.

A number of micro parties have already indicated their support for the plan, including the organiser of the Alliance for Progress (a group of progressive minor parties) James Jansson, who told the ABC in March that they wouldn’t be preferencing the Greens in the lower house.

However, just one month after the meeting, the alliance remains far from united in its plan.

Fiona Patten, a member of the Victorian Legislative Council and the President of the Australian Sex Party, says that they’ve yet to decide the contents of their how-to-vote cards.

“We don’t tend to go into these alliances in any formal way … the Sex Party will do its own thing and we will look at what’s strongest for us and what we think is right for us regardless of what the alliance will do,” Patten tells upstart.

“We will have to preference one over the other, that’s for certain.”

She says that frustration within the minor parties at the way voting reform was handled is driving the push to avoid the coalition and the Greens.

At the moment, particularly within my party, there’s a lot of discontent with the way the Greens have sided with the conservatives and the Liberal party to try and prohibit parties like ours from getting elected again,” she says.

“We’ve had no conversations with Labor or the Greens.”

Diaa Mohamed, founder of the Australian Muslim Party, also says his party have yet to make any preferencing decisions.

“It’s up for discussion, but right now after the party preferencing changes that Turnbull has introduced I’m not sure which way we’ll go,” he tells upstart.

Bruce Poon, a committee member for the Animal Justice Party, says the reforms are likely to make the “under representation” of minor parties in the Senate worse, but that his party haven’t made any decisions yet.

“The smaller parties are already under-represented in comparison to their vote share, and this change will probably make that worse,” he says.

“We have not finalised our position on who we will be preferencing. The Senate voting reforms are an important consideration, but there are also many other animal specific issues that we will be taking into account.”

As one of the largest progressive minor parties in Australia, the Sex Party’s preferences could play a pivotal role in hampering the Greens’ campaign to take Melbourne’s northern corridor from Labor.

This was the case at the 2012 Melbourne state bi-election, where the Sex Party managed to take just under 7% of the inner city vote, directing their preferences to Labor, who won the seat by a 3 point margin.

Ms Patten has indicated that her party will be running a candidate in Batman, with a high probability that they will also run candidates in Melbourne, Wills and Higgins – three seats that the Greens are contesting Labor for.

How much influence do minor parties have?

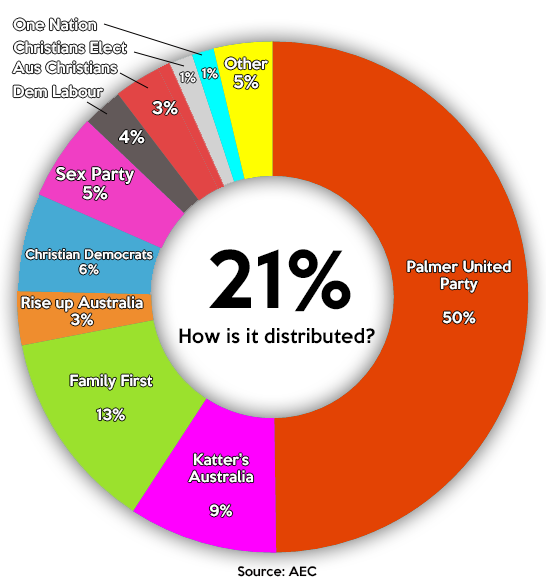

Support for minor parties and independents dramatically increased in 2013, with votes for non-major party candidates in the lower house accounting for 21.1% of all votes. In the Senate the number was even larger, with 32.2% of votes cast for non-major party candidates.

These figures may be deceiving though as more than half of the non-major party vote went to independents and the Palmer United Party, who have since been abandoned by two of their three senators.

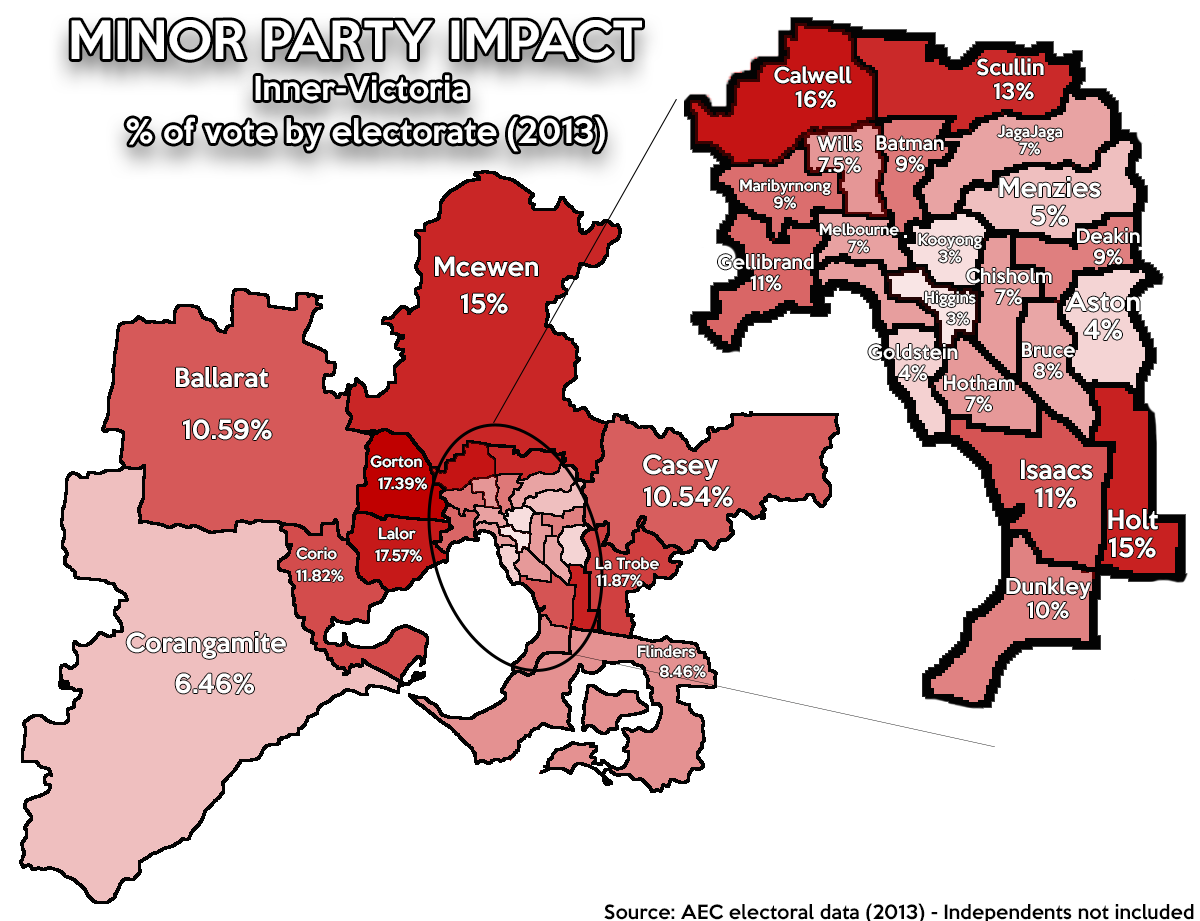

Whilst minor parties still don’t draw enough of the vote to meaningfully affect the result in safe seats, there are certain electorates where circumstances amplify their influence considerably.

These seats are characterised by an above average level of support for small party candidates and a tight margin between the ALP and the Coalition.

For instance, in 2013 Family First attracted 3% of the primary vote in the South Australian electorate of Hindmarsh. Not only is that more than double the party’s national average of 1.2%, but the Liberal party only won that seat by 3.8% – assisted by Family First preferences.

It’s in electorates like this that the Minor Party Alliance hopes to swing the result.

However, parties themselves don’t actually set preferences in lower house elections. Instead they formulate “how-to-vote” cards that they distribute to voters that list their chosen preference order.

In contrast to the Senate voting process that allowed minor parties to make preference deals largely without voter involvement, how-to-vote cards aren’t binding, which leaves preferencing decisions firmly in the hands of voters.

Which seats are being targeted?

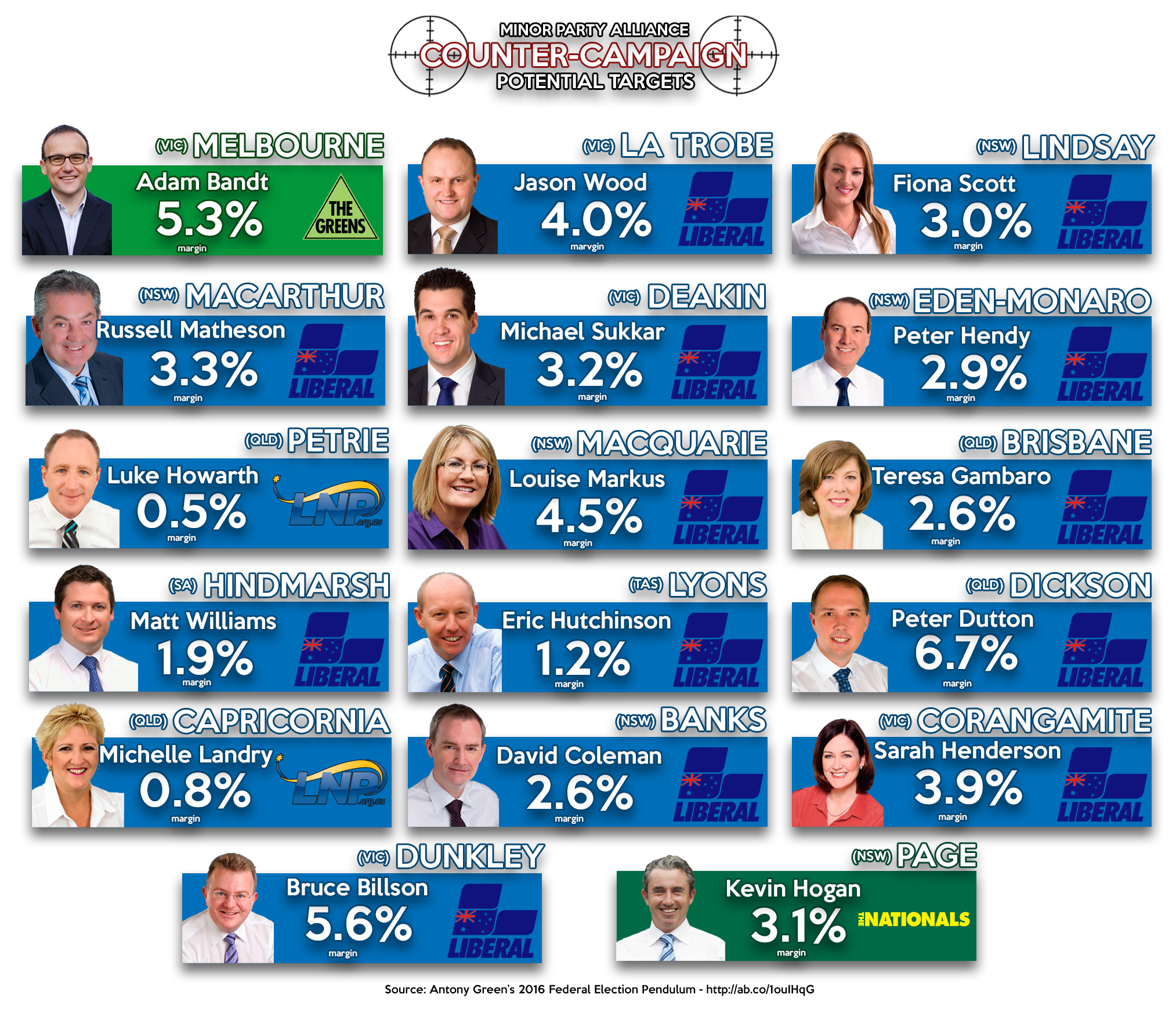

The list of proposed targets has changed since Druery first showed ABC’s 7:30 report a paper list of seats. Since then reports on which electorates will be targeted have varied.

The alleged targets are mostly marginally held Coalition seats, with the exception of Melbourne, which is held by the Greens’ Adam Bandt.

The list of targeted seats that have been reported include:

The Labor Party’s seats Richmond (NSW), Grayndler (NSW), Macquarie (NSW), Sydney (NSW), Batman (VIC) and Wills (VIC) have also been targeted for campaigns against the Greens.

James Jansson, leader of the Science Party and Robert Brown MLC of the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party did not respond to a request to comment on their preferencing plans.

Matthew Elmas is a final year student of Politics, Philosophy and Economics (majoring in Journalism) at La Trobe University, the current Politics and Society editor, and part of the UniPollWatch team. You can follow him on twitter: @mjelmas

Matthew Elmas is a final year student of Politics, Philosophy and Economics (majoring in Journalism) at La Trobe University, the current Politics and Society editor, and part of the UniPollWatch team. You can follow him on twitter: @mjelmas