From humble beginnings to one of the fastest growing sports in the world, Victoria was just another notch on the belt of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) – the world’s premier fighting company.

In March last year, Australian mixed martial arts (MMA) took a significant step towards legitimacy when the Victorian government overturned its ban on cage fighting.

This allowed the UFC to come to Melbourne and deliver one of the most historic and record breaking cards (UFC 193) the company has ever held – a success that saw $102 million injected into the Victorian economy and expand the UFC’s reach into a sport-heavy market.

The Labor Government banned cage fighting in 2008 over concerns it sent a message of violence. This resulted in MMA fights being contested in a boxing ring which was deemed less safe by fighters at the time.

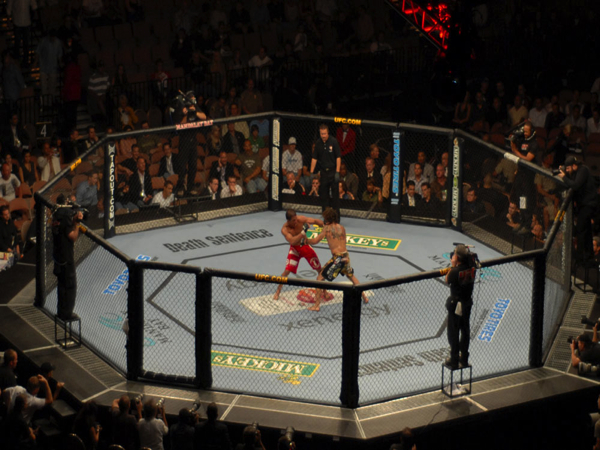

The UFC (which has been pushing for the law to be reformed in Victoria) uses a cage, otherwise known as an ‘octagon’, and has never held a bout in a ring.

One year on, the overturning of the cage ban has been welcomed by many, with Melbourne based MMA fighter Jordan Lucas saying fighters should never have fought in a ring in the first place.

“We should never have been fighting in a ring, it’s much more dangerous. You were seeing people falling out of the ring a bunch of times,” he tells upstart.

“I’ve actually never fought in Melbourne inside a cage, all my fights in Melbourne were in a ring.

“But as for other fighters it has definitely been a massive lift for the Melbourne MMA scene, Melbourne fighters were underrated for a while for that reason,” he says.

Editor of Fight! Magazine Australia, Jarrah Loh, says the UFC doesn’t play around when it comes to changing minds and educating others.

“This is what they do. They go around, they have a strong history of overturning government [decisions] all around the world. It was just a matter of time [before the Victorian government changed theirs],” he tells upstart.

Loh says although fighting in a ring was the norm for Victorians, it’s not the standard for professional MMA fighters around the world.

“If someone is used to fighting in America, the UK or Europe and they’re a professional MMA fighter, they fight in a cage every single weekend and come to Australia or Victoria and they’re fighting in a ring… it does make a significant impact on your gameplay,” he says.

“The way things happen in a fight as well. If you get someone to clinch up against the cage it’s like getting up against the wall.

“That’s a massive part of the MMA game. If clinching against the cage is not there it goes up against [ropes] so really it does change the fight and the tactics a lot fighting in a ring.”

The cage fighting ban hindered the growth and promotion of mixed martial arts in Victoria, however the sport has gradually gained popularity at the grassroots level.

Australian Fighting Championship director Adam Milankovic says since the overturning of the ban he has seen an increase in women attendances and children getting involved.

“The amount of females that love the sport and are getting involved with it just turning up to our events… you’ll see probably 40 per cent of the crowd are women and it’s good,” he says.

“Even kids at 14, 15 years old they come and they [want to] prove themselves, that they can compete in mixed martial arts.”

Loh says a common misconception among the public was that MMA fighting was banned altogether.

“People assumed for a long time, they probably still do that there was an actual ban on MMA when in fact it was just a ban on fighting in a cage,” he says.

Melbourne Lord Mayor Robert Doyle was one of the prominent advocates against the overturning of the cage fighting ban.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea to put two grown-up men in a cage and encourage them to beat each other’s brains out,” he said in 2015.

Loh believes the public may find it difficult to understand the sport especially if they’re not schooled in the rules of MMA.

“In terms of cage I think it’s a visual, the visualisation of it and people having this thing where people will be locked in a cage fighting to the death,” he says.

Loh says that this may impel people to view MMA as a no rules completion.

“People have the stance that it’s a Neanderthal sport or something like that. That there’s very little skill, that it promotes violence.

“I think the government of the time was too scared of a backlash. That’s what it was and then the government came in and saw it the opposite. They saw it as an opportunity.”

The UFC’s long-term goal now is to establish a company in each country that would run itself and answer to the parent company, according to Loh.

“There would be UFC Australia, UFC England type thing,” he says.

“I think there would be regular Australian events happening all year around and that the new UFC Australia or something similar would be its own established company obviously linked to the parent company.”

The UFC has certainly left its mark on Victoria, opening the possibility of the state hosting more events such as the UFC 193 in the future.

Last November’s UFC 193 at Etihad Stadium set an all-time gross gate record of $9.65 million speaking to the popularity of the sport particularly in Melbourne, the sporting capital of the world.

In July, the UFC showcased its rising popularity and commercial power when it was sold to new owners for $US4 billion, riding the momentum as one of the fastest growing sports in the world.

Western Australia remains the only state that has a restriction on cage fighting in place, and WA Labor has pledged to overturn the ban if it wins the next state election.

Jerwin De Guzman is a third year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University and a staff writer for upstart. Twitter: @jdeguzman_17

Jerwin De Guzman is a third year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University and a staff writer for upstart. Twitter: @jdeguzman_17