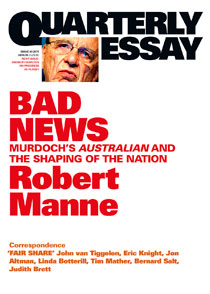

Between academic Robert Manne and our esteemed national broadsheet The Australian, an argument has erupted over the newspaper’s place in public debate.

Between academic Robert Manne and our esteemed national broadsheet The Australian, an argument has erupted over the newspaper’s place in public debate.

Both parties have clearly stated their positions: Manne in his Quarterly Essay, and The Australian in its response. Both use the evidence of the paper’s columns in support of very different arguments, with almost no points of agreement.

Few readers have the time to trawl back through years of broadsheets to see which argument is best supported by evidence in the form of The Australian’s coverage of particular issues. But what one can do is read both sides of the argument with a healthy, critical eye.

As readers and critics we bring our own perspective to the debate, perspectives that can influence the manner of criticism we offer. Let me outline the angle from which I approach this particular issue.

I grew up in Perth, where the local daily is the The West Australian, a tabloid sized paper owned by Seven West Media and usually considered to have conservative leanings. Unlike many of my peers who were raised in Melbourne, The Australian was essential to my media diet throughout my late teens and adult life. While many Melbournites I know dismiss it and turn immediately to The Age, years of habit and a desire for a national focus mean that as a reader, my broadsheet loyalties still lie with The Australian.

My upbringing in what some easterners might see as the backwater of Perth has not stopped me from being able to engage critically with what I read. The Australian’s manner of depicting certain issues has rankled with me for some time.

This feeling came to a head during the 17-day period following the 2010 federal election, when The Australian consistently depicted the figures of the hung parliament in a manner that favoured the Coalition. The most obviously misleading example of this was the inclusion in Coalition figures of Western Australian National Party MP Tony Crook, in spite of his explicit statement that the Coalition could not necessarily count on his support. With control of the parliament hinging on a few independents, this none-too-subtle shaping of the facts and prodding of public opinion was dishonest.

In spite of this, I do not embrace Manne’s arguments uncritically. I felt that his argument about Larissa Behrendt over an injudicious tweet was not developed convincingly. I’m aware that I am not in a position to judge those criticisms of The Australian that relate to earlier this century, due to the fact that I was younger and less politically engaged at the time. For example, I take Manne’s argument over the Iraq war with a grain of salt, as my own knowledge of the issue is insufficient to allow me to be appropriately critical.

On the other hand, I was able to consider Manne’s argument about the paper’s coverage of climate change in the light of my own experience as a reader, as it is a topic that I have followed closely over the last few years. This exercise in critical thinking is essential to navigating the conflicting arguments of Manne and The Australian.

This brings me to the discourse of left-wing versus right-wing that is so dominant in political commentary. The constant labelling of public figures as one or the other implies a lack of critical thinking and unquestioning loyalty to a limiting ideological perspective.

A large part of The Australian’s criticism of Manne is that he has swung from the right to the left, as though his loyalties miraculously shifted from one ‘side’ to the other. Manne’s apparent swing can be construed quite differently if this absurdly limiting spectrum is taken out of the picture; rather, his views can be seen to have evolved with time and experience, accompanied by a rare willingness to own and acknowledge this shift.

The Australian openly adopts a particular ideological point of view when it comes to political, social and economic issues. The problem is that some of the paper’s columnists seem to neglect critical thinking – that essential tool which allows one to change one’s opinion as an issue evolves – preferring instead to delightedly adopt any piece of evidence that dovetails nicely with their predetermined ideas about how the world should work.

Manne gives an example of this in his discussion of The Australian’s treatment of the Rudd government’s Building the Education Revolution stimulus program. In spite of the program’s general success, with complaints arising from just 3.1% of all schools involved, the paper consistently represented it as an unqualified disaster and as proof of the dangers of big government.

The reaction from many of The Australian’s commentators to Bad News has been polarising, implying that one is either with Manne and against The Australian, or vice versa. The paper’s editor, Chris Mitchell, attributes ‘Green values’ to Manne, and since The Australian has in the past openly argued in support of the destruction of the Greens at the ballot box, one assumes that Manne’s ideas must be similarly destroyed.

This attitude is utterly unhelpful. The world does not split neatly into: on the one hand, Greens, leftists, latte-sipping inner city elites and humanities academics, and on the other, rational, hard-working, ‘real-world’ Australians. There is a complex range of views in our society, a range which the paper says it gives voice to in its op-ed pages even as its own rhetoric of left versus right continually denies this complexity.

On some issues, The Australian is capable of representing a variety of views. On others, such as on its own role in Australian political debate, the paper seems quite unwilling to engage critically or productively.

Both Paul Kelly and Chris Mitchell have labelled Manne’s criticism as attack. This is another rhetorical bad habit, found on both ‘sides’ of the issue. There is a vast difference between critique and attack, and to blur the boundaries between the two does a disservice to public debate.

As I have said, I am a loyal reader of the paper. In spite of this I do not trust much of what I read in its pages, both news and opinion, aware that there are often holes in the paper’s coverage or commentary. This makes me uncomfortable. Yes, debate is and should be uncomfortable, but not because our only national, general-interest broadsheet appears to be pushing its own point of view, with a frequent disregard for journalistic principles.

Suzannah Marshall Macbeth is a Master of Global Communications student at La Trobe University and a former member of the upstart editorial team. She blogs at equineocean and you can follow her on Twitter: @equineocean.