The lecture theatre was cramped with an assortment of people. Some smirked from their seats. Others watched in disgust at the chanting faces and banging fists that rattled the surrounding glass doors. At the front of the room, the woman at the microphone pleaded with the security guards to do something. They simply shook their heads and didn’t move.

The fists belonged to a group of students who had gathered at La Trobe University’s Bundoora campus to protest the university Liberal Club’s guest speaker, Bettina Arndt.

La Trobe is renowned for its radical past. But this protest, consisting of only about 20 people, was the most vociferous —and the first to make headlines—in many years.

La Trobe’s protest movements can be traced back as far as the institution’s beginnings. Melbourne University students had been politically active throughout the sixties, but when La Trobe opened in 1967 it quickly became the new face of student radicalism.

Increasing media coverage of war and an evolving global youth counterculture motivated a frustrated and newly informed young generation to challenge the status quo. This local activism, occurring alongside worldwide rebellions that mobilised 10 million people in Paris and led to the massacre of student protesters in Mexico, left former La Trobe student, Barry York, with the feeling that history was being made.

“We had a strong sense in 1968 that we were part of a global movement, which is quite extraordinary when I look back on it,” he told upstart.

By the seventies, students all over Australia had mobilised. An anti-Vietnam moratorium in 1970 saw roughly 100,000 people march through Melbourne’s city, arms linked and placards raised in the air. Five thousand Monash students and more than 800 La Trobe students participated. A combined special edition of student magazines – La Trobe’s Rabelais, Monash’s Lot’s Wife and Melbourne’s Farrago – was released in support of the Moratorium.

While La Trobe students participated in the city march, they were also organising action on campus.

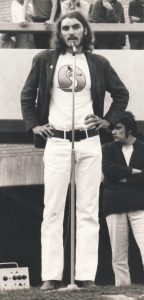

In September 1970, an anti-Vietnam War march from La Trobe to Ivanhoe Shopping Centre had been organised by the student Left. Roughly 70 people attended the march, but the young, long-haired crowd had only walked a block or two before the police arrived.

York, who participated in the march, says the police reaction was “incredible”.

“They stopped us marching on Waterdale Road, beat us up badly and chased us back to the campus,” he said.

Determined to not be silenced, the students quickly organised a second demonstration. A mass of 400 people attended, including the university chaplain and the media. Again, police bashed and arrested the students, unperturbed by observers. York remembers running towards the campus and hearing “stop or I’ll shoot”, while a fellow comrade stumbled behind, and was arrested at gunpoint, a level of police brutality not uncommon at the time.

Images of young people being dragged away and beaten appeared in the media, and one policeman was quoted as saying, “They got some baton today and they’ll get a lot more in the future.”

A third march garnered 800 people, including trade unionists who walked alongside the defiant students, flags raised. This time, the harsh criticism from the media and the chaplain meant that the police did not attack.

On campus, York would regularly thrust Labor Club and Communist Club leaflets into the hands of passing students outside the library in La Trobe’s student centre, the Agora—an image that any La Trobe student today would recognise.

He laughs at the memory of making announcements in Glenn College, to the annoyance of some students.

“Excuse me, sorry for interrupting,” he would say through a megaphone, “but we’re having a general meeting in half an hour’s time. Please come along.”

Footage from the time captures long-haired young adults filling the Agora, the university’s central meeting place, to listen to student leaders. Masses of students moved across campus holding megaphones, signs or burning draft cards. Buildings were shackled or scribbled with messages addressed to the university administration.

York remembers it as a time when the powerless were unafraid of challenging the powerful.

“There was a rebellious spirit at that time that’s hard to explain unless you were there,” he said.

In 1971, a general meeting held at Glenn College attracted 1000 students – roughly a third of the student population (50 times more than the Arndt protest). They voted for the resignation of Chancellor Sir Archibald Glenn, whose chemical company had ties to the Vietnam War and Apartheid South Africa.

That particular meeting was the turning point which unleashed campus action in the form of demonstrations, marches, blockades and occupations. On one occasion roughly 100 students used chains, padlocks and furniture to trap the university councillors inside of their meeting room. Many students were fined, expelled and even arrested for their rebellion.

The following year, the university identified four students as key leaders and issued them with restraining orders. Three of them – Brian Pola, Fergus Robinson and Barry York – defied the order and returned to campus. One by one they were thrown in the A Division of Pentridge Prison. The students, dubbed the La Trobe Three, were told they would be released if they apologised and promised to not return to La Trobe. They never apologised. York says this was a victory, despite the emotional toll prison took on him.

“We were guilty in that we did break the restraining order…but we were rebels, we were going to challenge any suppression of free speech,” he said.

The La Trobe Three were released months later, after signing a statement rejecting violence on campus. York continued to participate in student activism, but the events of 1972 signalled the end of a revolutionary era.

The shift to internal struggles

La Trobe maintained its left-wing protest culture in the decades that followed, but more quietly than the tumultuous early days. By the nineties, the political concerns of students had well and truly shifted from global issues to internal struggles.

In 1994 a blow was dealt to student politics when Voluntary Student Unionism (VSU) was introduced to Victoria. The controversial legislation restricts how student fees are spent and prohibits the funding of some aspects of student associations. This included student newspapers, which, prior to social media, were major platforms for students to voice their opinions.

VSU in Victoria was rolled back briefly by the Labor government in 2000, but legislation enacting VSU across Australia was passed in 2005. While left-wing campus groups such as Socialist Alternative were active during this time, former La Trobe Student Union President Clare Keyes-Liley believes the years of lost funding had a dire impact on La Trobe’s political culture.

“Howard and the previous liberal government wanted to shut down student activism and they did that through VSU,” she said. “It largely worked, because when I first joined on campus there was nothing.”

Funding was returned to student organisations in 2011 allowing the La Trobe Student Union to be formed. However, it still could not be used for political causes.

During a university break the following year, La Trobe announced a proposal to cut hundreds of subjects and fire 45 full-time academic staff.

Keyes-Liley found out about the hushed proposal from a lecturer. With two of her colleagues, she snuck into the lecture theatre where the announcement was being made and published the details on Facebook in real-time.

Many students were outraged by the announcement, which Keyes-Liley says was an entirely new experience. Rather than having to rely on the Agora or Rabelais, social media gave activists at La Trobe the power to reach more students and express their political concerns.

“The engagement that we got from students during that campaign was nothing like we’d ever seen,” Keyes-Liley said.

Aware that students were planning to protest the cuts on the coming Open Day, La Trobe Vice Chancellor John Dewar designated an area for protestors and threatened those who protested outside of the area with suspension or expulsion.

Unlike the students of the seventies who took loudly to the streets, Keyes-Liley and the LTSU were more cunning in their approach to protesting.

“We had t-shirts printed that said ‘if I protest today I will be excluded from La Trobe’ and on the back we wrote ‘ask me about the arts and humanities cuts’ and we were basically walking around campus speaking to parents about it,” she said.

Dewar’s warnings were also ignored by others, and a mob of protestors chased him into a building. News footage shows the Vice Chancellor struggling to move through the barricade of chanting students.

Soon after the protest, Dewar condemned the students in an article for the Conversation.

“These students’ behaviour was an abuse of the freedom of speech we had sought to preserve,” he wrote.

The collective anger that resonated across campus in 2012 brought education to the forefront of student activism at La Trobe. This provided momentum for 2014, when the Liberal government made a proposal to deregulate student fees, which if passed, meant that universities could charge students whatever they wished.

Thousands of students rallied across Australia in rejection of the Government’s plans. La Trobe student and Victorian Socialists Member Belle Gibson says the 2014 campaign against fee deregulation was the most significant protest she has seen at La Trobe and in Melbourne.

Education Minister Christopher Pyne – who was still pushing for deregulation – visited La Trobe the following year for a presentation. Roughly 50 students and union representatives protested outside of the presentation. Some tried to enter, but security pushed them away.

Where has it gone?

These days, campus action is still organised, but it doesn’t pull the numbers that it used to. Last August, students rallied at the University of Melbourne to support survivors of sexual assault. While more than 1000 people marked their interest or attendance on the Facebook event, barely a quarter of that showed up.

What inspired La Trobe’s protestors to show up in the past? Barry York says his dedication to activism was driven by rage.

“We were very outraged by the American aggression in Vietnam and by the Apartheid racist regime in South Africa, and the fact that our chancellor was connected to both meant that we gave focus to the campus as symbolic of the bigger issues,” he said.

Today, instances of inequality and violence are reported 24/7, and events can be organised with the click of a button. Why, then, is student mobilisation seemingly minuscule in comparison to the mass movements of the early seventies?

La Trobe student Taylor Tracy – who was unaware of La Trobe’s political culture until the Arndt protest – says that people today would rather communicate online than engage in physical protests.

“Social media brings people together from multiple locations and can address issues on a global scale,” she said.

“With that being said, it’s also easy to hide behind a screen instead of addressing issues in person.”

Barry York also believes the lack of secure jobs and housing might discourage young people from risking their education by engaging with political activism. In the late sixties and early seventies, Australia’s unemployment rate stood at two percent compared to the current rate of 5.1 percent, which is actually the lowest level of unemployment since 2012.

Belle Gibson agrees that these issues do play a part. However, she also believes it is the social attitudes that prevent large-scale campus activism.

“People of our generation, they don’t remember a time when ordinary people stood up and fought for themselves. And things are slowly getting worse, but there’s not this sense that there’s this sharp decline in our living standards and our rights,” she said.

Clare Keyes-Liley says that people will always find reasons not to engage with activism, and that while the ‘wins’ are important, what’s more important is finding a cause that will inspire people to get involved.

“I think it’s about finding what people are passionate about,” she said.

Gibson says the achievements of the La Trobe Three and their comrades gives her hope.

“It makes me feel proud because it’s like – okay, La Trobe hasn’t always been this sort of husk-degree-factory that it feels like at the moment – but also it gives me hope that things like that could happen again in the future,” she said.

She says protesting on campus is exciting and can give young people a sense of control over society.

“You feel like you might actually have the chance to change the way things are or you might have some direct power for the first time in your life,” she said.

But the future of student activism is uncertain. The NSW Government recently introduced laws which prohibit protesting on all crown-owned land in NSW. Since the Arndt protest, the government has announced an inquiry into free speech at universities, and future protestors could be charged for security costs.

In the face of such restrictions, could the mass mobilisation of the sixties and seventies ever happen again?

York says that while future mass movements are not impossible, the nature of campus radicalism has drastically changed.

“I don’t think there’s ever been another 1968…I haven’t seen that kind of rebellion, one that questions the fundamentals of society and capitalism,” he said.

However, Gibson believes the cycle will continue and students will eventually rebel.

“I think history has shown us that long periods of stability – like say the post-war boom after World War Two – are always followed by huge ruptures in society,” she said.

“[Australia] has stabilised significantly since a number of decades ago. However, capitalism is a system of crisis and nothing ever stays the same.”

She says political groups on campus will always be important as they are equipped to lead future movements.

“There still needs to be a campus left that capitalises on whatever radical sentiment is on campus and then is ready to push students into protest when things do start to get shaken up.”

Whatever the next big issue may be, Barry York encourages future activists to promote critical thinking.

“It is wrong to just be obedient…it’s right to question, it’s right to rebel.”

Shannon Jenkins is a third year Bachelor of Media and Communications (Journalism) student at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter @shannjenkins7

Images: Waterdale Road protest, Barry York and Herald billboard provided by Barry York. Bettina Arndt protest provided by author.