Subsequent to the Royal Commission in 1991, Aboriginal deaths in custody have increased by 150 per cent, which accounts for 340 dead people.

Peter Boyle from Australia’s Green Left Weekly newspaper told teleSUR, “Most [of the deaths] could have been prevented if the [commission’s] recommendations were all implemented.”

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody spanned from 1987-1991. As a result of the increasing numbers in such deaths, The Australian Government called for a study of the underlying social, cultural and legal issues of Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders.

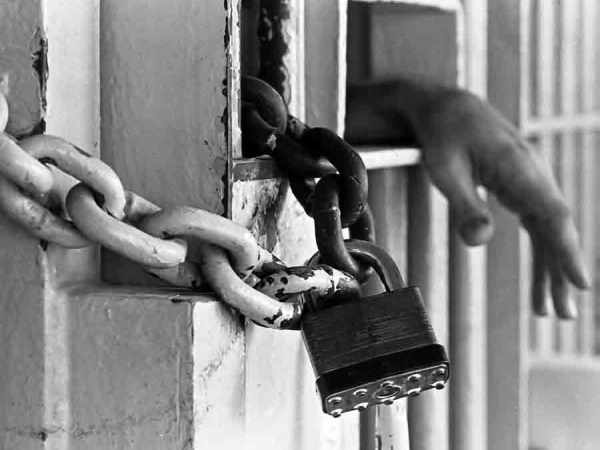

Upon examining the deaths of 99 people who had died in custody between 1980 and 1989, the New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania commission found that 13 out of the 18 deaths across these states could have been prevented had custodial authorities not been negligent, uncaring or had followed procedures adequately. The remaining five deaths may also have been avoidable on the grounds that these people may not have needed to be in custody at all.

A total of 339 recommendations were made, including:

- Arrest people only when no other way exists for dealing with a problem.

- Imprisonment should be utilised only as a sanction of last resort.

- Police and prison officers should seek medical attention immediately if any doubt arises as to a detainee’s condition.

- Initiate a formal process of reconciliation between Aboriginal people and the wider community.

“One of the key lessons of the Royal Commission was that Aboriginal people are not more likely than non-Aboriginal people to die in custody, but they are more likely to be in custody in the first place,” Jonathon Hunyor, the principal legal officer of North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA) told upstart.

As of 2011, Aboriginals make up 3 per cent of Australia’s population; however 28 per cent of the prison population are Indigenous. Colin Campbell from the Australian Institute of Criminology told upstart, “To explain the overrepresentation you also have to take into account the issue of severe disadvantage for so many indigenous people – and it is the unemployed, those with poor educations, poor health outcomes, homeless people, and people with addiction problems who are represented in the Criminal Justice System. They don’t have the education or the funds to avoid jail.”

“For many Aboriginal people and communities in the Northern Territory, imprisonment has become normalised and a large number of people; particularly men, but an increasing number of women, are in prison at any one time”, said Mr Huynor of NAAJA.

This, of course, imposes a number of difficulties in family and community life. Prison rates for Aboriginal women have increased by a third between 2002 and 2007, leaving many families affected by the loss of parents, role models, childcare and family income.

Forcibly removed from her family at age two as a victim of the Stolen Generations, Vickie Roach spent much of her life in and out of prison.

In 2003, Roach was sentenced to five years in prison after driving the getaway car after her then partner committed a robbery.

However, being a victim of domestic abuse was not taken into account at court and she now has a “violent offender” record.

“When they talk about ‘tough on crime’ they mean ‘tough on Aboriginal people’,” Roach told Al Jazeera, “If anyone thinks there’s any rehabilitation going on, they need to think again,” she said.

Seven years on, Roach is a women’s prison rights activist and still feels as though prison is the only experience she’s had that’s worth talking about.

“Locking more people up and locking them up for longer has become a default response, despite the evidence showing that it doesn’t make our community safer,” Mr Huynor said, “It is more likely to make the problem worse: imprisonment is criminogenic; it causes crime.”

Cecilia Distefano is a third year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University. You can check out her blog and follow her on Twitter: @cecilc0re